The term depth of field is common

One of the first things photographers learn about depth of field is that it is controlled by the aperture. This is correct but incomplete information. There are other factors that govern the depth of field. These are:

- The size of your camera’s sensor,

- The distance you are from your subject,

- The focal length of the lens.

Managing these variables well allows you to set a shallow or a deep depth of field. How you combine these has other effects when taking photos. Aperture settings are part of what influences how photos are exposed. Sensor size and focal length combinations produce different compositions. So does the distance you are from your subject. Being aware of these variables and how they interact with each other helps you take better photos as well.

Once you’ve learned to control the depth of field, you’ll be able to take more creative and interesting photographs. Getting the right amount of depth of field in a photo requires practice and experimentation. You need to know and understand what factors contribute to the depth of field and how to manage them. But first, let’s take a closer look at what depth of field is.

You are correct in thinking that this topic of depth of field is complicated. In this article, I’ll explain each aspect of managing it as practically as possible. I’ll include links for more details that may not be so practical to most, but may interest the technically curious.

Contents

What is the Depth of Field?

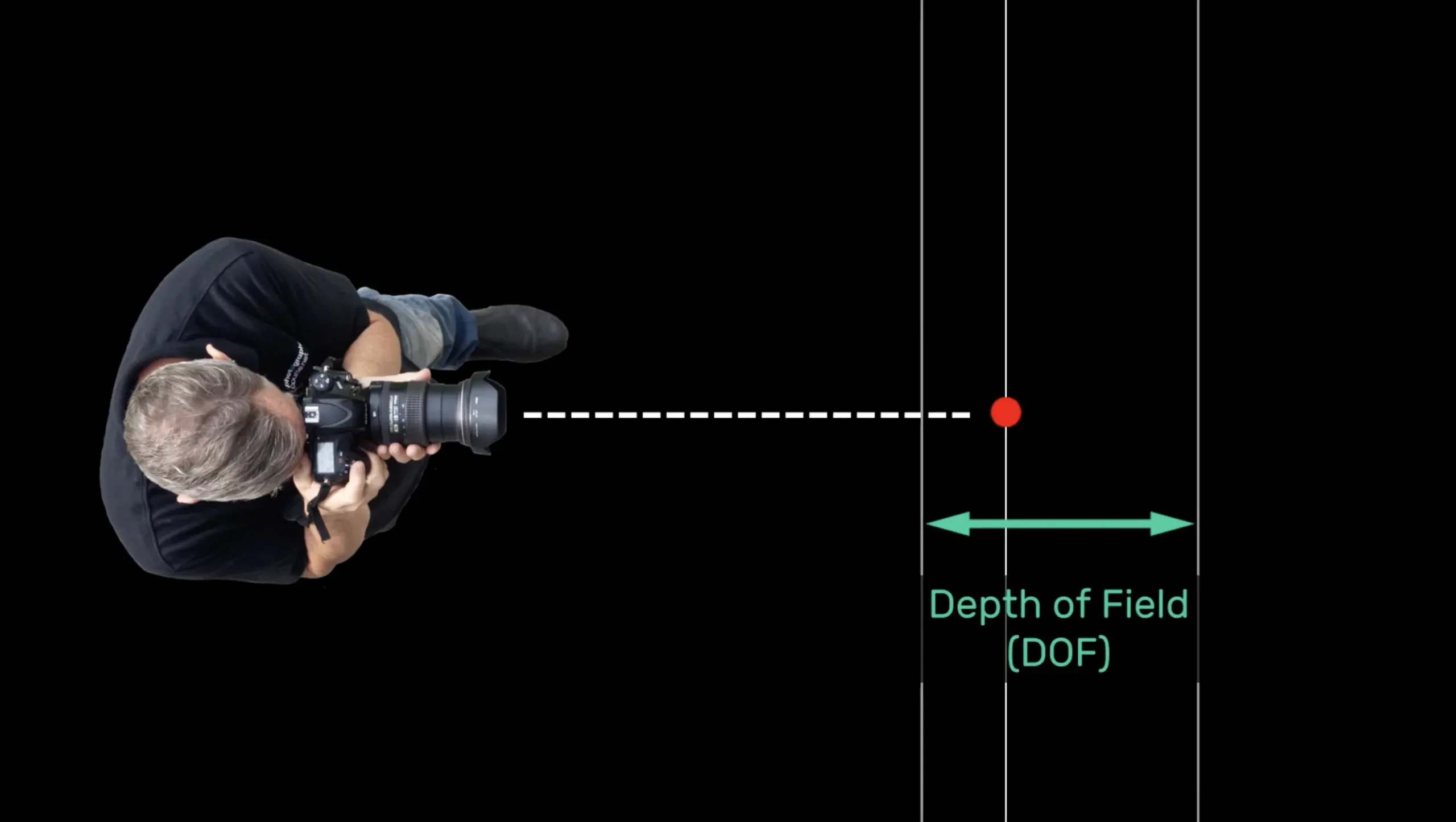

Depth of field refers to the distance, from closest to farthest, in a photo that appears to be acceptably sharp or in focus. It denotes the extent of the photograph that is in focus. When you focus your lens, everything at the same distance from your camera’s sensor will be precisely in focus. Anything closer or further away will not be so sharp. But whatever is ‘acceptably sharp’ is within the depth of field.

Imagine the point you focus on being on a plane that’s parallel to your camera’s sensor. Whatever is on that plane and within your composition will be sharp. Whatever is closer to you or further away will not be so sharp. The change from sharp to blurred is not abrupt.

Points closer to the plane are sharper than those further from it. Sharpness decreases the further from the focus plane a point is. So, elements closer to the plane where you have focused are going to be sharper than those further from it.

This is true regardless of any of the other variables that control the depth of field. How much is “acceptably sharp” is determined by the variables I outlined above. Further into this article, I will walk you through how to best manage these variables and explain more about them.

What is considered acceptably sharp is not black and white. The depth of field in a photograph never abruptly begins or ends. The transition between what is sharp and what isn’t is gradual. This is called the circle of confusion.

Some images with a very deep DoF will have no noticeable circle of confusion when most of the photo is acceptably sharp. Certain types of

- Landscapes,

- Cityscapes,

- Group portraits,

- Vehicles,

- Products,

There is no definitive list of subjects that require being photographed with a deep depth of field. Used well, depth of field is a creative aspect of

Let’s say you are looking at a landscape image that has everything in focus. This is an example of a deep depth of field. Landscape photographers often prefer to have as much of their pictures in focus as possible.

Deep Depth of Field

From the rocks and ice chunks in the foreground to the highest peak of the mountains in the background, this image is acceptably sharp. There is no obvious focus fall-off or circle of confusion.

I wanted to render as much of the scene as sharp as possible. I achieved this using a wide lens and a narrow aperture setting, despite focusing so close. My focus point was on the large chunk of ice closest to the camera. Even though my focus point was very close, the face of the glacier, which is a long way in the distance, and the mountain peak, still appear to be sharp.

Shallow Depth of Field

In this street portrait, the subject’s face, and more specifically her eyes, are in focus. Most of the foreground and the background are out of focus. This is an example of a shallow depth of field.

If her friend in the foreground and the market in the background were all sharp, you would be distracted from the main subject. Using a very shallow depth of field, I have isolated her, so she is the center of attention.

Both photos above were taken on cameras with full-frame sensors. The lenses used were different but had a similar focal length. The ISO and shutter speed settings make no difference to the depth of field. The different aperture settings have a significant influence on how sharp it is. So does the focus distance.

In the landscape photo, my point of focus was much further away from me than in the street portrait. The narrower aperture is not the only difference between the two photos affecting the DoF, and being further back from the chunk of ice when I focused means that more of the foreground and background is sharp enough. This is an aspect of depth of field that is often not taken into consideration.

There is more to managing depth of field than creating photos like these, which I have used as examples. DoF is not only about getting very little or the whole of an image in focus. By managing the variables well, you can create the right amount of focus for every photo you take.

Sometimes you may want a background completely blurred. Other times, you may want elements in the background of a photo partially blurred. So they are recognizable but not sharp. In other photos, your foreground can appear extremely blurred, and your background can still retain some soft detail.

Which Factors Affect Depth of Field?

In this section, we’ll take a look at which factors combine to affect depth of field and how you can best manage them to create the look you want in your photos.

Factors that affect the depth of field include not only the aperture value. Camera sensor size, the focal length of the lens, and the distance from the subject to the lens also affect the depth of field. The f-stop is the first, and sometimes the only, contributing factor to the depth of field that many photographers learn about.

The more skilled you become at combining the variables that contribute to DoF, the stronger your images become. You’ll not always want a very deep or very shallow depth of field. By managing each of the contributing factors, you have a great deal of control over how much of your photo will be in acceptably sharp focus.

Controlling the F Stop to Adjust Depth of Field

The F Stop, or F-Number, denotes the lens aperture setting. This is the size of the opening the diaphragm in your lens is set to. Every lens has this adjustable opening. It’s part of the exposure triangle and is used to help regulate light entering the camera. It also affects the depth of field.

The narrower the opening, the higher the f-stop, the deeper the depth of field. Less light will also be able to enter the camera. The wider the opening of the diaphragm, the lower the f-stop, the shallower the depth of field. More light will also be able to enter the camera.

In this article, we are looking at depth of field, so I won’t go into how aperture settings affect exposure. To learn more about this, please take a look at these articles.

When you want to take a photo with a deep depth of field, you are best to choose a narrow aperture. That’s one with a high f-number. The smaller the aperture diameter, the deeper the depth of field.

Taking photos with a very shallow depth of field requires a large aperture. That’s a low f-number. The wider the aperture diameter, the less of your photo will be in focus.

F-stop numbering is confusing when you first encounter it. Having a basic understanding of this system of measuring the opening of the diaphragm is helpful. You will make more informed choices about DoF when you understand the fundamentals of aperture size numbers.

The actual definition is a relationship between the focal length and the opening of the lens diaphragm. The F-number is expressed in fractions such as f/2, f/4, f/5.6, and so on. How wide the opening is with any lens depends on the focal length of the lens.

The wider the aperture values (lower f-numbers), the less area of the composition is going to be in focus. So the depth of field is narrow. On the flip side, if the f-number is larger, the depth of field is deeper.

In other words, when the f-stop number is small (f/1.4 or f/2.8), the DoF will be shallow. Only a small range of the subject will be in focus, but more light will be reaching the sensor. When the f-stop number is large (f/11 or f/16), the DoF will be deeper, and more of the image will be in focus. Much less light will reach the sensor.

Being able to manage the f-stop setting well, you can better control how much of your photo is in acceptably sharp focus. However, you also need to work with the other factors that contribute to depth of field, as it’s not all about the f-stop you choose.

Key Tip

Exactly how much is in focus cannot be measured solely by the f-number. You need to consider the other variables also. It’s easy to remember, though, that the lower the f-stop number, the less will be in focus. The higher the f-stop number, the more will be in focus.

The Effect of Lens Focal Length on Depth of Field

The focal length of the lens is also a contributor to the appearance of depth of field. A longer focal length lens will produce a shallower-looking depth of field compared to a wider lens. That is one reason landscape photographers prefer using wide-angle lenses.

Consider taking a photo with a 200mm lens and a 50mm lens on cameras with the same size sensors. Both lenses are photographing the same subject. They both are focused on the same distance and have the same f-number setting. The photos taken with the 200mm lens have a shallower depth of field than a photo taken with a 50mm lens.

The composition will also be a lot different. This is because the longer focal length lens crops in tighter when at the same focus distance as the 50mm lens. Elements at different distances from the camera also appear closer together with the longer lens. Telephoto lenses have the characteristic of compressing depth in compositions.

The greater the difference in lens focal length, the more noticeable the variance in DoF is. Distances appear more compressed the longer the focal length of the lens being used. This also contributes to the appearance of the depth of field being shallower at any particular aperture setting.

These factors make it more challenging to achieve a deep depth of field when using lenses with long focal lengths. As the focal length increases, the depth of field looks shallower. This is why you don’t often see close-up photos of dangerous animals with a deep depth of field. The photographer has to use a longer lens to keep their distance. So they get a shallow DoF.

Key Point

Some technically oriented photographers argue that the depth of field is the same with longer focal length lenses as it is with wider lenses. I prefer to explain

How Does Subject Distance Affect Depth of Field?

The closer what you are focused on is to the camera, the shallower depth of field your photo has. The further away you focus, the deeper the depth of field your photo has. This relationship with subject distance is true for any camera and lens combination.

How focus distance affects depth of field is more obvious in some types of photography than in others. In macro photos, only a small part of the main subject might be sharp. This is because the camera-to-subject distance is very short. So, even when you set your f-stop to the highest number when you are focused very close to your subject, you may only have a very shallow depth of field.

When you want to isolate a building or tree in a landscape, it can be challenging to create a shallow depth of field. You need to back up from your large subject so you can capture all of it. The more you back away and increase the focal point distance, the more your image will look acceptably sharp.

Even with a standard prime lens, like a 50mm set at f/1.4, you may not achieve a shallow depth of field. When you are far enough away from your subject to include it all in your frame, you will have a deeper DoF. Using a wider focal length lens allows you to get closer and include the whole subject. But you’ll still be challenged to create a shallow depth of field because of the wider focal length lens.

If space allows, backing away from your large subject and using a longer focal length lens is an option. If there are obstructions, then getting further back may not be practical.

Key Tip

The closer you are to what you focus on, the shallower the depth of field is. The further back you are from what you focus on, the deeper the DoF is. This is true no matter what combination of lens, aperture setting, and sensor size you use.

How Does Sensor Size Affect Depth of Field?

Sensor size has a major influence on the depth of field. The larger the sensor in your camera, the shallower the depth of field it captures. This has nothing to do with the number of megapixels, which is sometimes confused with sensor size. It’s the physical dimensions of the sensor that are relevant.

With any lens set to the same aperture, the photos taken on a larger sensor have a shallower depth of field than those taken on a smaller sensor.

Let’s say you are using two cameras: one a full-frame camera and the other an APS-C DSLR. You are trying to compose the same photo with the same focal length set to the same aperture. With the APS-C camera, you will have to step back away to capture the same composition. This happens because the smaller sensor effectively only sees a small section of the composition. When you step back, the depth of field increases.

The smaller the sensor size, the more difficult it becomes to take photos with a shallow depth of field. This is why phone camera manufacturers build workarounds. Because a phone’s sensor is so small, it cannot easily produce photos with a nicely blurred background.

When you use your phone to focus very close to your subject, you can sometimes create a shallow DoF. A background far away from your subject will mean it looks more blurred. But to take a portrait, you can’t get that close. The background will not be blurred.

Phone cameras now have apps or other means of computation that often blend photos to mimic a shallow depth of field. More than one lens takes the photos for the portrait. One will purposefully render the background out of focus. These photos then merge together to make a portrait with a blurred background. This works better sometimes than others. When it doesn’t work well, you end up with terrible-looking shallow DoF.

Key Point

If your camera has a small sensor, you need to manage the other variables when you want to achieve a shallow depth of field.

Managing Depth of Field

Juggling aperture size, camera-subject distance, and lens focal length might seem a bit much when all you want to do is take a few photos. If you’re interested in doing more than taking snapshots, it is important to manage your camera technique for mastering depth of field. Knowing the style of photo you want certainly helps figure out the desired depth you produce in any picture. A photo with a deeper DoF looks remarkably different than a photo of the same subject with a shallower DoF.

Taking time to learn and practice with the basic equipment settings, you’ll soon be able to create great photos. Each one has as much of the composition as sharp as you want it to be. You’ll be able to do this with any given focal length lens and minimize or maximize depth as you think best suits each photo you take. Deciding the style of images you want to take helps you determine how much depth of field to incorporate into your photos.

Is it important for the closest and farthest objects to be in sharp focus? Will your main subject stand out enough if you use a small aperture? Will decreasing the shutter speed help you maximize the depth of field?

How Much Light is There?

One of the first considerations has to be how much light you have to work with. Aperture size not only influences the depth of field but is also part of your exposure calculation. This means the aperture size you set makes a difference to how much light hits the image sensor, not only to the depth of field.

In low-light situations, you may want to take photos where the entire image is sharp. Managing your camera settings in low light is often more challenging. To obtain a greater DoF, you’ll need to work with small apertures. This will mean balancing your exposure with a slow shutter speed and/or a higher ISO setting.

On a bright sunny day or in other situations when there’s a lot of ambient light, it can be challenging to create photos with a very shallow depth of field. You’ll need to work with your aperture setting to ensure a good exposure. This can mean having to use a small aperture when you want to choose a large aperture. Setting a faster shutter speed and/or a lower ISO will help control the exposure and allow you to use a wider aperture.

Sometimes in these situations, you will not be able to open your aperture wide enough and still maintain a decent exposure. This is when decreasing the camera subject distance or using a telephoto lens can help.

Attaching filters to the front of your lens can help reduce the amount of light that hits your sensor. Adding a neutral density filter will allow you to open your aperture wider. This type of filter blocks a certain amount of light from entering the lens without affecting picture quality. Various strength filters are available, some blocking more light than others.

These are popular with landscape photographers. They allow them to use slower shutter speeds to capture blurred movement in waterfalls to create a silky look. You can also use them to reduce light entering the lens, meaning you can use a wider aperture setting for a shallower depth of field.

So you need to be mindful of how aperture affects not only depth of field but also exposure. This is why so many photographers prefer working in aperture priority. It helps them manage their camera settings more easily. In aperture priority mode, the photographer chooses the f-stop, and the camera manages the shutter speed. Doing this supposedly means you don’t need to think about your exposure as the camera manages this for you.

Key Point

I do not find aperture priority particularly satisfactory. This is because the camera does not know what you are photographing. It also never knows what your intent for your photos is. Manual mode provides you with more flexibility in both exposure settings and image sharpness. It doesn’t take long to learn to use manual mode when you set your mind to it. When you practice and learn a little frequently, you can master your basic equipment settings in no time.

Bright Light Portrait with Shallow DoF

I photographed my friend using an 85 mm f/1.4 lens. I wanted to isolate her and the tree stump, so I set my aperture to f/1.4. Because the sun was so bright, this was challenging. The early morning light was beautiful, and I wanted to make the most of it, but I also wanted a very shallow depth of field.

Hoping to maintain the widest aperture setting I could, I dialed down my ISO. I’d had it set at ISO 400 and ISO 800 with the cloud cover. For this series of portraits, I set it at ISO 100. I adjusted my shutter speed to 1/8000th of a second, the fastest option on my Nikon D800 camera. I was able to capture the photo with a very nice exposure. The background is completely blurred, but my friend and the tree stump are acceptably sharp.

Even though in this lovely location, there was very little in the background. We were far away from everything except grass and a few decaying tree stumps. I’d already made many photos with more in focus. So I wanted to experiment with a shallower depth of field so the colors in the landscape would feature more in the portraits I was making. The softness of the background also helps enhance the beautiful texture of the wood.

What Lens is Best for this Subject?

Sometimes you have many options for what focal length lens you can use for a photo. Other times you will not. Photographing wildlife and sports matches generally requires the use of a long focal length lens. You’re hardly likely to capture a photo of an aggressive grizzly bear with a wide-angle lens and live to tell the tale of it. At times, wide-angle lenses are not appropriate to use, so you are challenged when you want to take photos with greater depth.

In situations when your options are more open, you can choose which lens to use based on how you want to compose your subject. You can also pick a lens with a wider f-stop to help you get a very shallow depth of field. If you are photographing products or portraits, you have more choices about which lens to use.

Think about what you can frame with a lens at any given focus distance and how this affects the depth of field. Sometimes it might be better to move back and open your aperture up. This can give you the same depth as having a closer focus point and using a wider aperture diameter. You’ll need to keep in mind the crop factor of your image sensor when choosing which focal length lens to use.

Zoom lenses typically do not have such wide maximum aperture settings as prime lenses do. This limits your options when you’re aiming for a shallow depth of field. My wife prefers to photograph with a zoom. I like my prime lenses. Her main lens is a lovely 24-120mm f/4. I have a 35mm f/1.4, an 85mm f/1.4, and a 105mm f/2.8.

These lenses are within the range of the focal length of her zoom. But each prime has a wider aperture setting, which allows for a shallower DoF. Whenever we are taking portraits together, I have to be quick if I want to use the 105mm. This is because she prefers this for portraits because of the wider aperture.

With macro

My Favorite Lens

My favorite lens is my 35mm f/1.4. It’s fantastic for environmental portraits. I love it because I can come in close to my subject and still have a reasonable amount of the background in my frame. Being close to my subject as I photograph them, I am at a natural distance to have a conversation with them.

Like the 105mm, using a longer lens would mean I have to be much further back to capture the person and some of their surroundings. This makes it more difficult to chat with a person as I am taking photos. Because my 35mm has the widest aperture setting of f/1.4, I have more control over my depth of field choices. When I want to completely blur a background, I can. If I want to have the background out of focus, but not totally blurred, all I need to do is close the aperture a little more.

When I want a very deep depth of field, I can close the aperture down even more and back up from my subject somewhat. Taking these two steps will increase how much of the photo is in focus without otherwise altering the composition too much.

Depth of Field and a Kit Lens

Most kit lenses are limited because the widest aperture is not very wide. The aperture in kit lenses is also fixed. As you zoom in, the opening of the diaphragm remains the same size. This is why you will see two maximum aperture numbers on cheaper zoom lenses.

At the widest focal length, the maximum aperture might be f/3.5. While zoomed to the longest focal length, the widest aperture setting may be listed as f/6.3. This is because the f-stop measures the size of the diaphragm opening relative to the lens focal length.

Higher-quality zoom lenses have one maximum aperture setting. Often this is f/2.8, so still not as wide as many prime lenses. The size of the diaphragm opening on these lenses changes as you zoom. These lenses are bigger and heavier because of this. The size of the glass elements that make up the lens needs to allow for a wider aperture. The longer the lens, the greater the diameter of the glass elements needs to be.

Creating photos with a deep DoF using your kit lens is not a problem. It’s when you want to reduce how much of your image appears sharp that it is challenging. At the widest zoom, which may be 24mm or wider, f/3.5 is not going to knock much of your background out of focus (unless you are very close to your subject).

Typically kit zooms will have a longest focal length of 55mm or sometimes 105mm. At f/5.6 or f/6.3, you will still be challenged to manage a shallow depth of field. Being close to your subject and focusing on them from the shortest distance possible will produce the shallowest depth of field. This is true for any lens. It’s the limited aperture setting that makes it more challenging with a kit zoom.

Using prime lenses with a very wide aperture provides you with more flexibility. You don’t always need to use the widest aperture setting just because your lens opens up that wide. Sometimes f/1.4 or f/1.8 produces a depth of field that’s too shallow. You need to get a feel for what the most appropriate DoF is for any picture you are taking.

Why It’s Important to Control Depth of Field?

You can isolate your subject using a very shallow depth of field. You can create a deep depth of field when it’s important to have the closest and the farthest objects sharp. Controlling the depth of field in your photographs can help convey meaning and produce the desired atmosphere.

Having the equipment to allow you the most choice makes a difference. As I discussed above, some lenses afford you more flexibility than others. Often, these lenses may not be easy to afford. The wider the aperture setting on a lens, the more expensive it is. So you need to learn to manage the gear you have to capture the style of photo you want.

Portraits with shallow depth of field help draw attention to your subject. A tree, building, vehicle, or any other subject can be made the center of any composition when you isolate it by using a shallow DoF. To do this in a diversity of situations, you’ll need lenses with wide maximum aperture settings (often called ‘fast’ lenses). A camera with a large sensor, rather than a small one, will also help.

When you work with a full-frame camera or a larger sensor and fast lenses, you have more options available. Setting how much of your images are in focus is easier. With a camera sensor that’s smaller than full-frame and a kit lens, your options are more limited. The smaller sensor and narrower maximum aperture mean you’ll not be able to achieve a shallow depth of field so easily. You will not likely have a problem when you want to capture a deeper DoF.

Any time you want sharp images with a maximum depth of field, you can control this. Sometimes it means landscape

Your intent is what makes the difference — knowing how you want your photo to turn out guides your choices for how you will control the depth of field. But it’s not only a matter of choosing between a very shallow depth of field or a deep depth of field. Being in control of how much of your image is sharp allows you to create more interesting compositions.

Key Point

At times, you’ll want some of what’s behind your subject to be blurred, but not so blurred that it becomes unrecognizable. Creating a bokeh is not always what’s most important.

Too much depth of field can distract attention from the main subject. Too little depth of field can eliminate too much relevant information. Finding a balance where what’s in the background is visible and recognizable but not invasive is superb depth of field management.

Tips for Managing Depth of Field

Know What You Want

Having a clear idea in mind for how you want your photos to turn out is one key to becoming a successful photographer. Part of this is knowing how much of each photo you take to be sharp. Leaving this to chance does not help you produce more creative photos. Instead, it will lead you in the opposite direction, and you’ll end up with a higher percentage of images you throw out.

These decisions made consistently will add to your personal

When you know how much of an image you want in focus and why, you can then control your settings and where you take the photo to achieve the result you want. When you don’t know what you want to achieve, you’ll often be disappointed with the photos you take. The more knowledge and skill you have, the more you will know what you want. Frequent practice of techniques until you are confident with them will speed up this learning process.

I find studying the images of successful photographers whose work I admire helps me gain inspiration for my own

Online browsing of photos is also helpful if you are purposeful and slow down enough to appreciate the photographs. There’s a tendency to scroll through photos very quickly when viewing them on a computer or electronic device. This behavior does not help build your appreciation of good

Key Tip

Deciding how you want a photo to look before you take it gets easier with practice. The more you photograph the same types of subjects, the better you’ll get. You will know instinctively how you want to photograph your subject, so the pictures will turn out the way you want them to. Pick up your camera every day and take a few photos. By doing this, you will become more familiar with it.

Learn a little each day, even for a few minutes. Put what you learn into practice. This will speed up your progress towards being confident with your camera.

Choose the Best Combination of Lens, Distance, and Aperture

Both of these photos were taken at the same market using the same camera and lens. I used my Nikon D800 with my 105mm f/2.8 prime.

For the first photo of my friend looking to buy flowers, the location is important to the photo. I wanted to show where she was as well to illustrate what she was doing. My focus was on her, and I wanted to make sure she stood out from the background. This was challenging because the market is a visually busy place. This is also relevant to my photo, so I didn’t want to have it completely blurred.

I set my aperture to f/2.8 and kept enough distance so the background would still retain some detail but would not be sharp.

This photo was made using the same aperture setting. I did not want so much detail visible in the background because it was not relevant. I moved closer to my subject, and the background was further behind her than in the photo above.

The closer the focus distance, the smaller the depth of field. The distance my subject was from the background means that what was behind her was more out of focus. Less of this photo is acceptably sharp because of the distances, even though I used the same lens and aperture setting.

Manage Your Focal Length

Purposefully choose which focal length lens you will use, partly based on how much depth of field you want. The lens you use has a strong influence on the depth of field and composition in general. You can make or ruin a photo opportunity with your lens choice.

Wider lenses include more of a scene and also show more focus compared with medium and longer lenses. A medium lens captures less of the scene while providing you with more options for a shallow or deep DoF. Longer lenses reduce your field of view and compress the distance between elements in your frame. This contributes to the appearance of DoF. It’s more challenging to capture a lot of composition in sharp focus when using a long lens.

Think about how far away your focus point needs to be with any given focal length lens. Let this factor into your calculations because focus distance affects the depth of field. You may want to compose a scene in a certain way with a shallow depth of field. But you cannot with a medium lens because you can’t move far enough back. When you compose the same scene with a wider lens, you may not be able to achieve such a shallow DoF.

Getting a feel for how the various focal length lenses you use capture depth of field helps you make decisions about focal length more quickly. This is one reason I like to work with a limited number of prime lenses. Sure, I am limited in focal length options more than if I used a couple of zooms, but there are fewer variables to consider.

I have a sense of how much is going to be in focus at any given aperture when using my 35mm lens, or my 85mm, or 105mm. These are the lenses I use most frequently, so I know that at a certain distance from my subject, I’ll have as much in focus as I want at any particular aperture. I could not tell you the measurement of the DoF because I sense what I think is the right amount.

The hyperfocal distance of a lens is helpful to know when you want a deep depth of field. When you want to have as much of your composition in acceptably sharp focus as possible, you need to know the hyperfocal distance. When focused on the hyperfocal distance, any lens at any set aperture will produce the deepest DoF it can. This varies from lens to lens depending on focal length, so it’s great that there are apps for smartphones to calculate this for you.

Key Tip

Try sticking to using one focal length or a limited range on your favorite zoom lens. Start with a medium focal length of about 50mm or the equivalent of a crop sensor camera. Only use this length for the next one or two hundred photos you take. Or at least until you are more familiar with it and how the DoF looks at various aperture settings and distances.

Once you are comfortable with this, choose another focal length and do the same. You may be surprised at how helpful this is in getting to know the characteristics of your lenses.

Two Different Focal Lengths

I changed the lenses between these two photos. The wider lens was my 35mm, with the aperture set to f/2.8. The other photo was taken with my 105mm, also with the aperture set to f/2.8. I was about the same distance from my friend.

You can notice that the appearance of the DoF is different, mostly in the water and the trees. I had changed my point of view slightly between the two portraits. The trees in the photo taken with the 35mm lens are further away than the ones in the portrait made with the 105mm. They look less blurry in the 35mm photo than in the 105mm photo, despite being further away from my subject.

Choose the Most Effective F-Stop

Set the f-stop to achieve the style and amount of blur you want. This will depend on the effective focal length of the lens you’re using and the crop factor of your image sensor. You will get used to this when you practice often. (See above.)

Many photographers think of depth of field management as only about what aperture setting they choose. You have already learned that the f-stop you set is only a part of the equation that determines how much of any photo is acceptably sharp. Picking the best aperture setting to create the look you want takes time and practice. You get a different look depending on the focal length you’re using. So it is not as simple as choosing the same aperture setting on one lens that you used on one of a different focal length. The results will be different.

The most effective f-stop is one that gives you as much of your image in focus as you want. This may be a little or a lot. Or it might be somewhere in between.

When you only want a little in focus, the obvious choice is to open the aperture as wide as possible. Creating photos with a deep DoF will lead you to choose a narrow aperture setting and calculate the hyperfocal distance. Deciding the ‘in between’ is more complicated.

The distance your subject is from what’s behind it and is in your frame influences how focused it will appear at any particular aperture setting. For example, if you have a 50mm lens on your camera and focus on a subject 2 meters away with an aperture of f/5.6. Something 10 meters in the distance will be more out of focus than something in the frame that’s only 2 meters behind your subject.

Key Tip

When concentrating on capturing the right amount of your image in focus, you need to consider all the variables that come into play. Thinking about controlling the depth of field using aperture settings alone does not provide you with the most control.

Think About More than Your Aperture Setting

To isolate one orange marigold flower, I used an aperture setting of f/2.2 on my 35mm lens. Had I used a narrower setting, too much would be in focus. It’s plane to see there are other marigolds in the background, even though they are so blurred. Our brain recognizes they are the same. Attention is given to the one flower in the foreground that is sharp, and this makes the composition more interesting.

I took the photo of the pink dahlia with the same lens and was about the same distance away from it as I was from the marigold. I used an aperture setting of f/11. The background is further away, especially in the top one-third of the composition, so it is nicely blurred.

Had I set a wider aperture, the depth of field would have been shallower, and the background would not have been recognizable. Had I backed up away from the flower and used an even narrower aperture, this would have increased the DoF. The background would not be blurred enough and therefore be distracting. The color contrast between the pink flower and green rice also helps isolate my subject well.

The distance I was from the flowers plays a significant role in the appearance of the depth of field in both of these photos. Had I positioned my camera further back from them to take these photos, this would have created a deeper DoF in both photos.

Close Means More Blur

Subject distance plays a significant part in capturing the best depth of field. How close or how far you are from your subject when you focus on it contributes to how much of the photo is acceptably sharp or blurry.

When you want a shallower depth of field, get in closer. Reduce the distance between you and your subject, and you’ll see less of the background in focus. This is true whether you’re using a wide-angle lens, a medium lens, or a telephoto lens.

No matter what aperture setting you choose, when your focus distance is short, your DoF will be shallower than when you are further back. So, when you want a shallow depth of field, even with a wider lens, get in closer to your subject. Be careful with very wide lenses and getting too close to your subject, as wide lenses will cause distortion. Keeping your subject in the center of your frame will help to minimize the risk of distortion.

When you are after more of your image in focus, move back away from your subject. The further back you are from what you are focused on, the more your image will be acceptably sharp. There will be more in front of and behind the point of focus that is sharp, the further back you get. Remember, though, that if you move back and use a longer lens to maintain the same crop as with a wider lens, this will affect the DoF.

Key Tip

The focus distance is one of the key aspects of depth of field management you can control when working with kit lenses. The widest aperture setting on a kit lens will rarely produce a very shallow depth of field. So getting in close makes it more effective when you only want a little in focus.

Close-up Orchid Flowers

In these three photos of orchids in our garden, the only change I made was to the distance I was from the flowers when I photographed them. The lens and aperture settings were the same for each. I used my 55mm micro lens with the aperture set to f/8.

In the closest photo, the focus distance was 25mm.

In the medium distance photo, I backed up and focused 50mm away from the flowers. My point of focus remained on the tip of the bottom-most petal.

The third photo in this series is about 100cm away from the flower.

You can see the difference in the depth of field when you look at the leaves behind the flowers. Resizing the images so the flowers are the same size in each, you can see the differences in DoF when you look at the flowers that are behind the one I focused on.

Here’s another example of distance from the subject affecting depth of field.

I took both these photos with the same camera, lens, and aperture setting. I had my 105mm on my Nikon D800. My aperture was set to f/5. The ISO was 400. The only difference in setting between the two photos was my shutter speed, which does not affect the depth of field.

In the photo showing more of my friend and the train, the shutter speed was 1/250th of a second. In the other photo, my shutter speed was 1/160th of a second. I used fill flash for both photos to help lessen the shadows on her face and balance the light on her and the ambient light.

She was in the same position for both photos. So the same distance from the train behind her. I took the first photo and then took a step or two closer to her. This alone made the difference in the appearance of blur in the background. Because I moved about one meter closer to her and kept my focus on her face, the depth of the field was reduced.

Key Tip

A depth of field calculator is a handy tool that shows you how much of an image will be in focus when combining the various contributing factors. This can help understand the depth of field.

Practice Managing Depth of Field

Like anything creative, the more you practice, the better at it you will become, especially when there are so many variables and options for how your photos might turn out.

Photographers are prone to not practicing. Our cameras are designed to make taking photos easy. But what is easy does not always result in the most creative results. Being as creative as possible with your camera requires understanding and practice. Repetitive action builds a habit, but as photographers, we tend not to do this as much as a musician has to.

Learning to play the guitar, piano, or any instrument, you must work hard. To be successful, you must develop good habits. These only come about by repeating the same pieces many, many times until you are proficient. It’s easy to be a lazy photographer and skip the practice because the technology we use for our craft will make an okay image for us, regardless.

Learning to manage depth of field well takes lots of practice. You need to concentrate on each aspect until you understand it and are confident in managing it well. Set your mind to learning to manage depth of field and work on a series of exercises. Repeat them, so the fundamentals of controlling depth of field become part of your subconscious as you are taking photos.

The more you rely on your automatic camera settings and are not in control, the more dissatisfied you are likely to be with the photos you take. Be determined to put into practice what you now know about controlling depth of field. It does not need to take long. The more you focus on learning and working at it, the quicker you will master the look you want for your photos.

Work on your understanding of focal length and how this impacts the depth of field. Use a zoom lens or a selection of prime lenses. Take photos using the same aperture setting and focus distance. Take a series of photos of the same subject using different focal lengths. Compare how the depth of field changes as you use different focal lengths.

Then use a single prime lens or one focal length on your zoom. Vary only the aperture settings, not any other variable we’ve discussed that affects the depth of field. Balance your exposures with your shutter speed and/or ISO. Check the differences in how much of your photos are in acceptably sharp focus at the various f-stops you have used.

Take time to make a series of photos where you get closer to and further away from your subject. Choose a subject you can move. Place it close to the background and then progressively further away from it. Keep your aperture, focal length, and focus distance constant. Check how much the blur in the background changes each time you move and take more photos.

Work through each of the variables I have outlined in this article and examples. Don’t think so much about making terrific photos while you are concentrating on practicing to master depth of field. Think of it like a musician must practice their scales. Repeat the same exercise over again until you are sure of what you are doing.

Once you have spent time working on each variable, then start to combine them. Decide how you want to compose each photo and how much of it you want in acceptably sharp focus. Challenge yourself, and don’t make it too easy. See if you can take the same composition with a shallow, medium, and deep DoF. You may be surprised at how easy it becomes to get precisely the images you want. It will not happen automatically. You must take your time and be dedicated to practicing and understanding what is happening each time you press the shutter release.

There Are No Set Rules

The depth of field is affected by many variables, so there is no set formula and no rules to apply. You must consider each situation individually each time you compose a photo. Not all portraits look great with a blurred background. Some landscapes make a more interesting photo with a shallow depth of field than a deep one.

When you understand the principles and know how to manage the variables, you are well-equipped to make your own choices. You’ll also recognize the limitations, and this gives you more freedom in how you choose to take your pictures. Knowing that the closer you are to your subject, the shallower the DoF, you will not be frustrated that you can’t take macro photos with more in focus. You have to manage the photos within the constraints of the principles.

The more you practice and consciously think about depth of field, the more your choices will become part of your subconscious. You will know instinctively how much you’ll be able to get in focus with a particular lens and distance from your subject. In situations where the light is changing or your subject is moving, this helps you make choices, and the setting changes more rapidly. This then increases the percentage of great photos you can take.

Think outside of what the rules tell you to do and what other people consider correct. There is no right or wrong in

Conclusion

Learning how to make the most of your camera and lenses by controlling the depth of field is a key aspect of taking your

Practice Exercise

The aim of this exercise is to teach you how you can control DOF.

| Lens: Standard | Exposure Mode: Aperture Priority |

| Focus Mode: Any | Location: Indoors and Outdoors |

- Choose your lens with the widest aperture setting that can be used at 50mm. This could be a 50mm prime or a zoom lens you can set at 50mm.

- Choose a subject where you have three or more objects about the same distance apart. You could photograph trees in a local park or line up three bottles or other objects on a table. Position yourself slightly to one side of the lineup so you can see each item.

- Set your aperture to the lowest f-stop number (widest it can open), focus on the object closest to you, and take a photo. Then, focus on the next object and the last one, making photos each time.

- Select an f-stop that’s about the middle of the range for your lens and repeat the three photos, focusing on each object in turn.

- Repeat again using the highest f-stop number on your lens, taking three more photos as you focus on each object.

- Use a tripod or increase your ISO setting if needed when using the narrowest aperture setting.

- Optional: Repeat all three series of photos with a wider lens and a telephoto lens if you wish.

Thanks. very informative especially to the novice like me. . .

Thank you

it is nice and i get good highlight about the field of study.

Thank you!

thanks! i love phtography!

Nice

Hi everyone, I was shooting landscape photography including person in the frame. I was using 55 to 200 mm lens. Whenever I was focusing the person, the background was getting blurred and whenever background was clear, person in the picture was dull. Am I using the wrong lens? Do I need wide angle lens to get clear background and clear person in the image together.

Yeah you should probably use a wider angle lens when shooting nature but also back away from the subject a little

Thank you

Brilliant guide. Thanks

Mark Wallace videos are good, always liked.